The English love spy novels. As much to remember their memories as to mythologise their national novel. Review of Most Secret Agent of Empire, Reginald Teague-Jones Master Spy of the Great Game.

Across the Channel, historical works on espionage and the Great Game are designed to appeal to the general public[1]. In the post-imperial era, the English spy remains a source of national pride, just like pudding or goose hunting. Never a dilettante, but always an expert, a sportsman at heart, an adventurer and a traveller, the English spy at the height of the British Empire inhabited the world. Beneath his pith helmet, he cast an impassive gaze, his knickers revealed firm, muscular calves, and he uttered pithy remarks with his legendary humour, without fear of appearing arrogant. This image, shaken by the recent release of Slow Horses, a series directed by Will Smith based on the novel by Mick Herron, which gives a rather disenchanted view of the famous MI5, is part of British ‘nation branding’ and is proving resistant to Britain’s loss of world power status.

Spy news

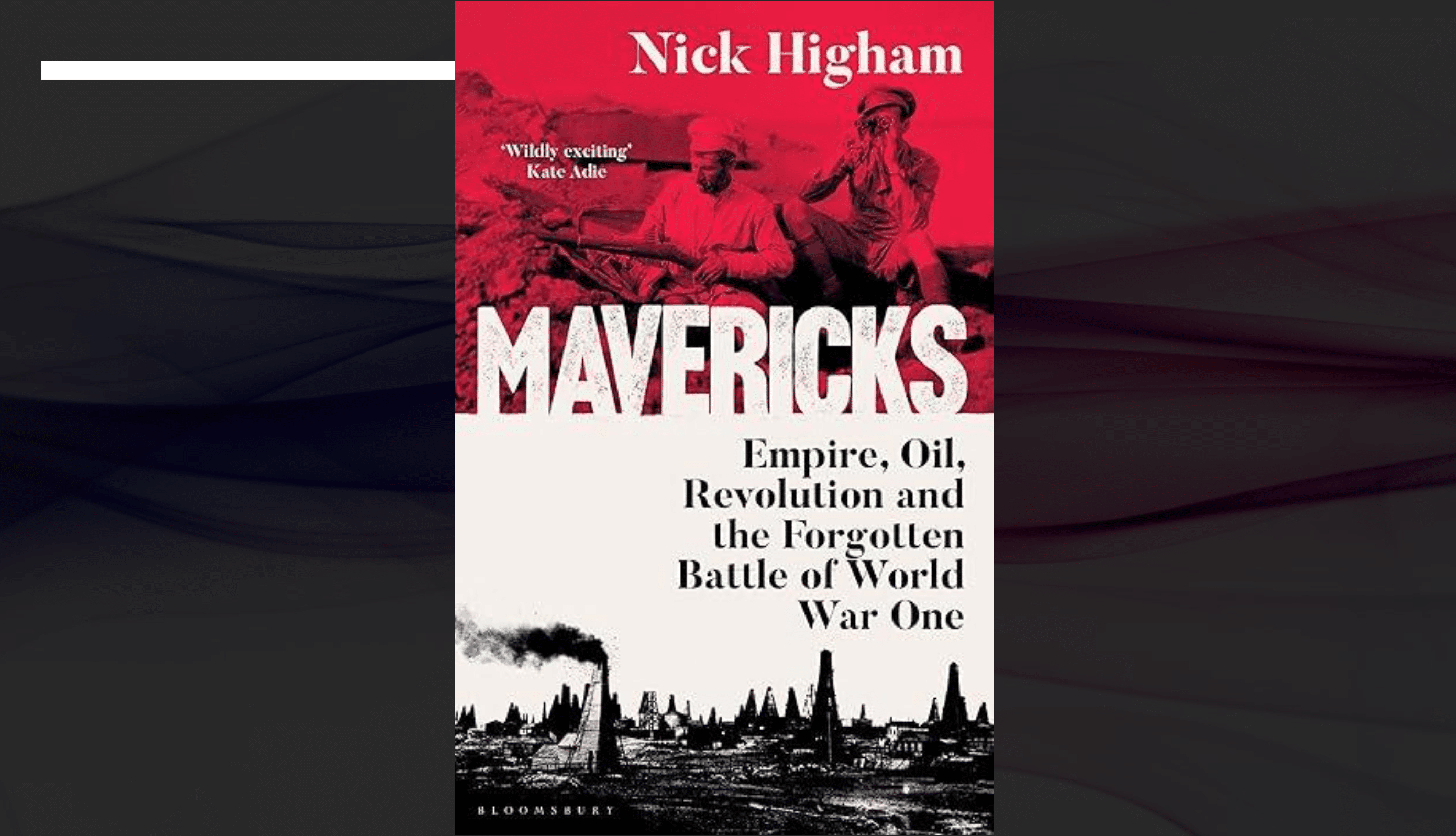

In Mavericks, Empire, Oil, Revolution and the Forgotten Battle of World War One (Bloomsbury, 2025), Nick Higham looks at a forgotten and notoriously inglorious episode of British involvement in the First World War. The author, a former BBC correspondent and author of a previous book on the issue of water in London, The Mercenary River (Headline, 2022), focuses on five British agents involved in various capacities in the complex theatre of operations that was Baku in 1918.

Writing this story is undoubtedly timely at a moment when relations between the United Kingdom and Azerbaijan continue to develop: on 5 November 2025, the meeting between Hikmat Hajiyev, advisor to President Aliyev, and British Minister Stephen Doughty led to the deepening of the strategic partnership between the two countries, announced on 25 August[2]. Nick Higham’s book is a timely reminder that the British have long been interested in Azerbaijan, when at the end of the First World War, the British authorities decided to send a disparate ‘group’ of spies and military personnel to the Caspian region, which was in chaos at the time. Their mission? Impossible, of course, as it involved blocking the advance of the Ottoman Turks, preventing the spread of an anti-British jihad among Muslims in India, containing the development of Bolshevism and, finally, securing vital access to Baku’s oil amid the general turmoil.

Baku, a geostrategic issue

Although Baku had been a symbolic war goal since November 1914, corresponding to the ideals of Pan-Turkism cherished by the Young Turks, the city only really became a strategic objective after the October Revolution and the collapse of the Caucasian front, which had been abandoned by Russian soldiers. In the breach left by the disappearance of the Russian army, War Minister Enver Pasha launched the Ottoman army in February 1918 with the aim of liberating the irredentist lands (Kars, Ardahan, Batum), raising the Muslim populations and marching on Baku and Central Asia.

In the confused situation in Transcaucasia in 1918, in the midst of civil war, foreign intervention and the provisional victory of national movements, Baku became a real strategic issue for the Turks, Germans, British and Bolsheviks. In order to contain the Turkish advance, the British attempted a reverse operation through Persian territory, commanded by General Dunsterville.

Meanwhile, the Germans, signatories to the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, agreed with the Bolshevik government to take control of Baku and its oil fields before the Turks could capture the city, a prospect that undoubtedly explains why the British considered destroying the oil facilities by aerial bombardment in early August 1918.

On the eve of Dunsterville’s entry into Baku, these plans were abandoned in favour of the simple pragmatic argument that such an operation would have permanently alienated the Tatar workers, already known to be pro-Turkish, from British power. The agreement concluded in Mashhad between the British and a short-lived ‘Transcaspian government’ to ward off ‘the danger of the Bolsheviks and the Turks and Germans’ once again demonstrates the importance attached to the defence of Baku, ‘gateway to Russian Central Asia, on which much of the economic life and military power of Russian Turkestan and Transcaspia depends’.

In exchange for strategic facilities granted to the British in the Caspian Sea – control of the port of Krasnovodsk and the Trans-Caspian railway – the British undertook to provide military aid to the Trans-Caspian government, to defend Baku to the last and to evacuate, as far as possible, stocks of fuel oil and naphtha to the other side of the Caspian Sea, in Krasnovodsk. A few weeks later, the capture of Baku by the Army of Islam led by Nouri Pasha (15 September 1918) was accompanied by massacres of Armenians and marked, a few weeks before the Allied victory, the height of the German-Turkish offensive in the Caucasus.

Five Mavericks

Nick Higham puts his journalistic writing talent to work in a book aimed at the general public: navigating his way through rich and complex historical material, telling the distinct stories of five agents of British power who, however, never formed a ‘group’, is in itself a daring gamble, one that the author largely succeeds in pulling off. For the ‘Transcaspian episode’, as it was named by Charles Howard ‘Dick’ Ellis[3], another MI6 agent whom Nick Higham curiously chooses not to focus on, is a veritable tragicomedy.

Who are they? First there is General Dunsterville, fictionalised during his lifetime by Rudyard Kipling, who recounts his schoolboy escapades in Stalky & Co. (1899). The mischievous Stalky was directly inspired by Lionel Dunsterville, who was placed at the head of the crazy land (and sea!) expedition known as Dunsterforce, which was supposed to travel from Baghdad to Baku in 1918. Dunsterville humorously summed up his epic crossing of the Caspian Sea in August 1918 in these terms: ‘an English general on the Caspian Sea, the only sea never before crossed by a British ship, aboard a vessel named after a South African president who was then an enemy, sailing from a Persian port, flying the Serbian flag, in order to deliver the Armenian population of a revolutionary Russian city from the Turks’[4].

Of Scottish descent, like many other agents of the Great Game in India and Afghanistan, Ranald MacDonell, 21st hereditary chief of the Glengarry Clan, is Nick Higham’s second Maverick. Appointed vice-consul in Baku in 1905, at a time when the first revolution in the Russian Empire was locally reflected in fierce ‘Armenian-Tatar’ wars, MacDonell became interested in oil and settled for a year in a pumping station in the middle of the derricks.

There he met, among others, a certain Stepan Chaoumian, Lenin’s right-hand man and later representative of the Soviet government in Baku. Then a certain Edward Noel appeared on the scene: he was the third Maverick, from a military family with aristocratic ancestry, a character burnt out from within, gifted with great political and scheming abilities, which, in a city like Baku, was in itself a kind of passport. In 1918, he was captured in northern Iran by the Jangalis (forest fighters) of Chief Mirza Kuchik Khan: a separatist, he was also a sympathiser of Lenin, who saw his republic of Gilan as the first step in the expansion of the revolution in the East. Noel survived his long months of captivity and managed to escape, but ended up an opium addict. The second son of the famous diplomat and Assyriologist Henry Rawlinson, who was one of the players in the Great Game in the 19th century[5], Toby Rawlinson, with his walrus moustache, thrived on adrenaline. His inveterate taste for sport and risk led him to all the theatres of war. From Baku, he moved on to Turkey to become, at his own risk, an informal ambassador for the British to Mustafa Kemal. Last but not least, the last Maverick is a boy from Liverpool. With no notable social ancestry, neither a baronet nor a Scotsman, Reginald Teague-Jones is the spy who disappeared to become Ronald Sinclair following the sensational affair of the execution of the 26 Commissars of Baku (20 September 1918) ‘by the British imperialists’ according to Soviet legend.

Nick Higham agrees that, of the five Mavericks, he is certainly the most extraordinary character. A free spirit, he grew up in Russia with an English family, was educated at the prestigious Annenschule in Saint Petersburg, already spoke four languages as a teenager, and witnessed Red Sunday in Saint Petersburg. But Teague-Jones is clearly the character who most disturbs Nick Higham, who refuses to believe his story entirely. The author’s disbelief is not exactly the critical spirit that historians apply to their sources. It focuses on minor details and discrepancies, which the author strives to demonstrate are ‘major’. In Nick Higham’s writing, Reginald Teague-Jones becomes an ‘unreliable narrator’ whose ‘lies’ the author strives to expose, as if this were not a necessary skill for any self-respecting English spy! If he is simply discreet about the circumstances of his romantic encounter with the young Russian woman who would become his first wife, does that discredit his understanding, and above all his account of the events of the Transcaspian chaos? Elsewhere, Nick Higham does not believe it possible that Teague-Jones, disguised as a merchant, could have smuggled a stamped secret map past the ‘authorities’ in charge of boarding a Transcaspian steamer crowded with refugees at the time of the fall of Baku. And the author deduces from this episode, which is nevertheless credible – because in Russia, especially in wartime, any map is by definition ‘secret’ – that the character is a self-fabricating liar.

This is the main flaw in the book: Nick Higham peppers his narrative with moralising judgements, stigmatises the inveterate imperialism of his Mavericks and accuses Teague-Jones of anti-Semitism without questioning the objective fact of Jewish participation in the Bolshevik revolution[6]. The author may be deliberately committing this anachronism. Or is he succumbing to the temptations of cancel culture? In any case, this is what has been retained in reviews of Nick Higham’s book published in the major British newspapers. Moreover, this hasty and, dare we say, misplaced judgement of Reginald Teague-Jones adds nothing to the central episode of his life as a British spy: the case of the 26 Baku Commissars. Here Nick Higham cautiously relies on the documents and works of historian Brian Pearce (1915-2008) and my own book. However, the other side of this murky affair lies in Moscow, in archives that are currently inaccessible. Archives that are undoubtedly full of precious lies.

[1] Most Secret Agent of Empire, Reginald Teague-Jones Master Spy of the Great Game, London, Hurst, 2014.

https://aze.media/uk-and-azerbaijan-upgrade-ties-to-strategic-partnership/

[3] Ellis, Charles Howard ‘Dick’, The Transcaspian Episode, 1918-1919, London, Hutchinson, 1963. See the book devoted to him by Australian author Jesse Fink, The Eagle in the Mirror: in Search of War Hero, Master Spy and Alleged Traitor Charles Howard ‘Dick’ Ellis, Black and White, 2023.

[4] Quoted in Taline Ter Minassian, Reginald Teague-Jones, Au service secret de l’Empire britannique (In the Secret Service of the British Empire), Paris, Grasset, 2012, p. 191.

[5] See Taline Ter Minassian, Sur l’échiquier du Grand Jeu, Agents secrets et aventuriers, XIXe-XXIe siècles (On the Chessboard of the Great Game: Secret Agents and Adventurers, 19th-21st Centuries), Paris, Nouveau Monde, 2023.

[6] See Yuri Slezkine, The Jewish Century, Princeton, Oxford, Princeton University Press, 2004.