Ankara has never rejected the possibility of a peace process with the PKK. The Turkish president, however, now intends to dictate its terms.

Article published in Issue N59 Droite. La nouvelle internationale ?

On February 27, 2025, Abdullah Öcalan, the imprisoned leader of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), called on the terrorist organization to lay down its arms. Two months later, the PKK, assembled in congress, announced its self-dissolution. A struggle lasting four decades seemed to be ending.

Scattered across Iran, Syria, and Iraq, the Kurds make up 20% of Turkey’s population. In 1984, the PKK, of Marxist-Leninist allegiance, declared an armed struggle aimed at creating a Greater Independent Kurdistan. But Öcalan’s capture dealt a severe blow to the organization.

Since then, sheltered in the Qandil mountains of northern Iraq, the PKK extended its influence. With the Syrian war, the Kurdish organization laid the foundations of a self-governed zone in Kobane. Intolerable in Ankara’s eyes, it challenged national unity. Now in a position of strength, Turkey has every interest in negotiating.

For Erdoğan, the conflict drains already battered finances due to rampant inflation. It is also a constant source of tension with Washington, which has long viewed the PKK as a lesser evil and an ally against ISIS. More still, the Kurdish question is Ankara’s Achilles heel, shamelessly exploited by the Russians, Israelis, and Iranians whenever it comes to containing Turkish ambitions.

Erdoğan the master of the game

In line with this low-intensity war, the peace taking shape is equally asymmetric. It designates a winner and a loser, and is therefore imposed on the weaker party. Since 2015, the date of the last ceasefire, Erdoğan has believed such a process would eventually settle the conflict, once the PKK was sufficiently weakened on the battlefield. Peace is always political in nature. It seals a balance of power. The enemy becomes, therefore, a partner to negotiate with. Even today, this Clausewitzian ambivalence can be seen in the Turkish president when he warns: “Should the hand we extend be left hanging or bitten, our iron fist remains ready.”

Erdoğan’s approach is dictated by four reasons:

Victory in the East: Since 2016, Turkey has deployed the Bayraktar TB2 drone, armed with smart micro-munitions and a modified UMTAS missile with an 8 km range. In just a few years, the proportion of casualties caused by TB2s skyrocketed—from 30% in 2017 to 70% in 2025. The conflict shifted. The days when the PKK could harass Turkish posts with impunity and inflict heavy losses on terrified conscripts are over. First, the Turkish army crushed the embryonic autonomous strongholds in the major southeastern cities. Then it swept the countryside, pushing the PKK beyond national borders. Under skies increasingly crowded with drones, the Kurdish organization was driven underground.

The Qandil mountains, on the Iraqi-Iranian border, became riddled with reinforced tunnels. Too busy surviving, the PKK abandoned offensive ambitions. At the same time, the militant manpower, the indispensable fuel for operations, dried up. Only a trickle of recruits still arrived from Iran. Above all, the organization disintegrated. Drones eliminated mid-level commanders aged 20 to 40, who bore the brunt of the fighting. Only the older ones, further removed, survived. As a result, the Party’s apparatus ossified.

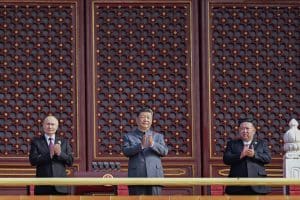

The impossible double game: Since the start of the Syrian war, the PKK played both sides. First, it exploited the benevolent neutrality of Russia and Bashar al-Assad by refusing to join the rebellion backed by Ankara. Then, under the cover of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), it enlisted under the Western coalition’s banner against ISIS. Since then, northeastern Syria hosted 2,000 U.S. special forces soldiers.

But this Russo-American double umbrella collapsed in autumn 2024. The Ba’athist regime’s collapse led to Russia’s departure and the reunification of Syria. Simultaneously, Donald Trump’s election aligned with a U.S. withdrawal in favor of Turkey, which the American president now sought to accommodate. Isolated and without room to maneuver, the PKK suffocated. Military collapse was compounded by geopolitical asphyxiation.

Continuing to govern: In Turkey, politics is first a matter of arithmetic. In essence, the country is split into two blocs: a conservative bloc and a secularist bloc. Between the two, the Kurdish vote tips the balance. In the last municipal elections, the Kurdish contribution was decisive in the secular opposition’s victories in Ankara and Istanbul. While Erdoğan knows it is impossible to win over this electorate en masse, he at least hopes for their neutrality. A shrewd calculation, as Kurds have refrained since the truce announcement from joining anti-government protests following the arrest of Ekrem İmamoğlu, Istanbul’s mayor and Erdoğan’s chief rival for the presidency. But to run for a new term, Erdoğan must first overcome a major hurdle: the constitutional ban preventing a third presidential bid. Without an absolute majority in the National Assembly, Erdoğan needs Kurdish MPs to amend the Constitution. A practitioner of transactional politics, Erdoğan never gives without receiving in return.

Reuniting Iraq, unifying Syria, and containing Israel: The Kurdish issue is the Gordian knot of Ankara’s foreign policy. A pawn in the manipulations of Turkey’s neighbors, the PKK is a festering wound blocking any rise to power. Resolving the conflict means first building bridges with Baghdad by restoring Iraq’s unity. On this momentum, Turkey hopes to advance its “development corridor” project, linking Anatolia to the Persian Gulf. In Syria, peace would consolidate the new regime in Damascus and thwart Tel Aviv’s efforts to keep the country weak and fragmented. For Israel, a Sunni and unitary Syria under Turkish protection would be a far greater threat than a fractured, Alawite-led Syria allied with a sanctioned Iran.

Pax Turcica?

Although the contours of an agreement remain vague, some points have begun to leak. Three key lines emerge:

The PKK unequivocally renounces all separatist or even autonomist ambitions, whether in Turkey or elsewhere. Öcalan himself declared the struggle for a “separate nation-state, federation, or administrative autonomy” obsolete. This is a major victory for Erdoğan, since it was the PKK’s very reason for existing.

A general amnesty for Kurdish militants would be declared, with the release of prisoners. Senior PKK figures would see prosecutions dropped in exchange for discreet exile abroad. As for Abdullah Öcalan, his fate remains undecided, though he might be released from İmralı Island prison to house arrest. With history in mind, the Kurdish leader imagines himself a new Nelson Mandela, the man who would reconcile Turks and Kurds.

A final point would end the state-appointed trusteeship over DEM (Halkların Eşitlik ve Demokrasi Partisi—the People’s Equality and Democracy Party), Turkey’s Kurdish party. Added to this would be measures expanding Kurdish language and cultural education up to a certain threshold.

Ultimately, Erdoğan, in a position of strength, imposes his peace. He also knows he can count on a significant fraction of devout Kurds who have always given him their votes. In speech after speech, the reis invokes Ottoman brotherhood-in-arms under the Islamic banner. He recalls the shoulder-to-shoulder fight against predatory Western powers in the aftermath of the First World War. What he does not say, however, is that if Turkism and Kurdism merge, this marriage will first and foremost serve the former.