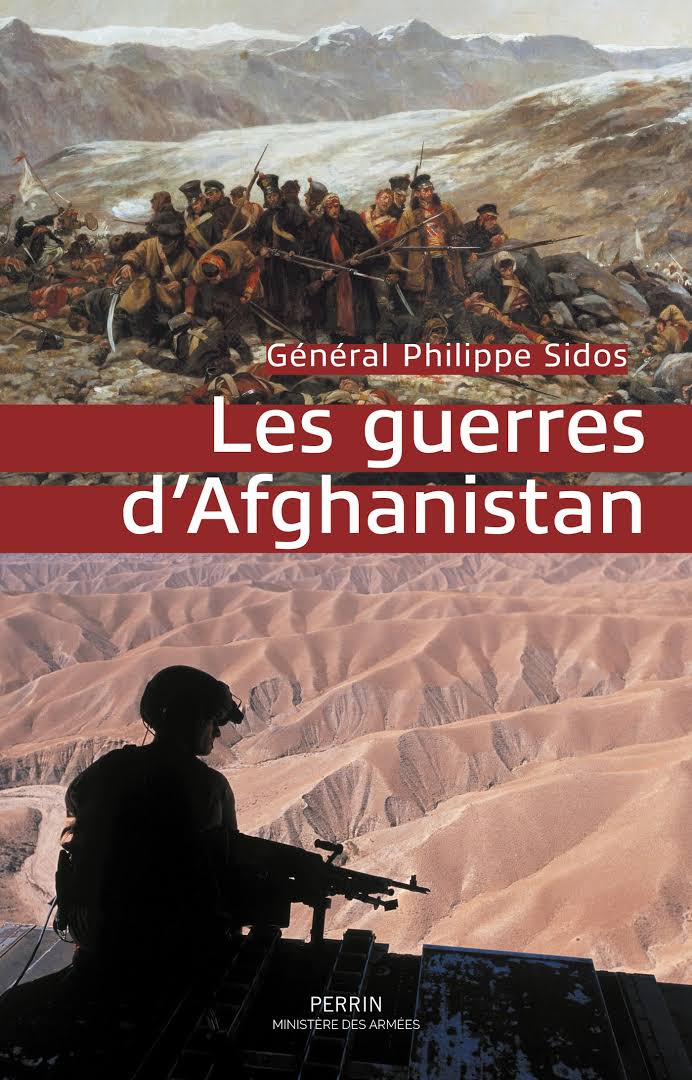

If you are looking for a comprehensive work on the history of Afghanistan, a country that has been in a state of almost constant war since the early 19th century, this joint publication by Perrin and the French Ministry of the Armed Forces should largely meet your needs.

The first line of the first chapter of this book sums up the entire chronological narrative of nearly 500 pages: “The history of Afghanistan is a military history. It is the story of a country that was almost constantly involved in internal conflicts and fought for its independence against expansionist powers.”

That pretty much says it all, because this fragmented, mountainous territory, divided both religiously and tribally, very quickly became the object of desire in what has been called “the Great Game.” This was the name given to the influence of Imperial Russia and the British Indian Empire.

The Anglo-Afghan Wars

We learn that the tensions unfolding in the north of the Indian Empire, but also in Persia, had direct consequences for Afghanistan. The local princes, themselves divided, had to deal with representatives of the British Empire who were seeking to secure the Indian subcontinent.

Afghanistan has been described as a graveyard of empires, and when we read the first part of the book carefully, we see that the United Kingdom, despite conflicting influences, was never really able to exert control over this territory. Even more seriously, multiple military disasters during the various Anglo-Afghan wars show that, despite the resources committed, and even if Afghan forces can be dispersed, they are never actually subjugated. In British military history, it took three successive wars to achieve a form of diplomatic stabilization in Afghanistan, a territory whose borders with Persia, among others, are not clearly defined, not to mention the northern part of the Indian Empire, where the Pashtuns are widely established.

The first Anglo-Afghan War began in 1838, and the British had enormous difficulty establishing themselves in this territory. The British army, retreating from Kabul on January 6, 1842, suffered considerable losses in the face of the Afghan insurrection. This episode had a lasting impact on British military leaders who, despite reprisal operations, eventually withdrew, at least temporarily, from the country. It would be 40 years before a new British army was deployed to Afghanistan. The Second and Third Afghan Wars were partly linked to the actions of neighboring princes, but also to Russian expansionism and internal divisions within the country. Once again, after the Sepoy Rebellion of 1857, it was the Indian Army that found itself engaged in combat. Once again, the British suffered another defeat on July 27, 1880, and once again, the British army had to retreat to Kandahar.

Contrary to popular belief, the Afghan army had access to some modern weaponry and even artillery. Beyond traditional ambushes, accounts of these clashes show that Afghan military leaders devised maneuvers in open terrain, obviously taking advantage of their mobility. Before the Third Anglo-Afghan War began, Lord Hartington, British Secretary of State for India from 1880 to 1882, explained that all that had been achieved by British intervention « was the disintegration of a state . »

At this stage, before the third Anglo-Afghan War, the British sought to stabilize the borders between the Indian Empire and Afghanistan, which was finally accepted in November 1893 with the Durand Line. Relations with Russia, which were able to play an indirect role with the princes of the north of the country, led to the Convention of Saint Petersburg, which was signed in 1907. The Durand Line, whose boundary had been set for a hundred years, stretches over 2,400 km and crosses the areas settled by Pashtun tribes between the Punjab and Afghanistan. This boundary was never officially recognized by successive Afghan governments, and in 1897, in the Waziristan area, multiple clashes involving nearly 35,000 men from the Indian Army took place. Emir Abdur Rahman played an ambiguous role, probably favoring anti-British insurrections in the northwest of the territory. He reigned for 21 years, from 1880 to 1901, leading numerous operations against the Tajiks and Uzbeks.

After World War I and the assassination of Emir Abdur Rahman’s eldest son, it was his third son, Amanullah, who expressed to the British his desire to achieve full independence. The very serious incident in Amritsar on April 13, 1919, put British forces in difficulty in the Punjab, leading the emir to conduct operations on the Durand Line. This marked the beginning, in May 1919, of the Third Anglo-Afghan War. Despite various initial successes, the British troops, composed of sepoys, also experienced mutinies. The British used a bomber on Kabul and finally Emir Habibullah requested peace, which was obtained following the Treaty of Rawalpindi on August 8, 1919.

This initial period showed, after these wars against Great Britain and despite the British victory in May 1919, that the Afghans could be defeated but never truly dominated. The British even gave up occupying Kabul and ultimately accepted a form of distancing from the empire.

Part Two: The USSR imposes itself and loses

From 1919 onwards, Soviet Russia, which continued the tactics of the Tsarist empire in this area, lent its support to the Afghan regime. The Soviets supported Emir Amanullah against Habibullah, who was accused of being a British agent. Habibullah had proclaimed himself emir and was unique in that he was Tajik, unlike all the emirs who had ruled Afghanistan throughout its history. Habibullah eventually prevailed, leading Stalin to withdraw the Red Army advisers in early 1930.

The new king of Afghanistan, Nadir Shah, managed to maintain a balance with the British, keep his distance from the Soviets, and forge relations with Germany, Italy, and Japan. However, Afghanistan remained neutral during World War II.

In the aftermath of World War II, and especially from 1953 onwards, the Soviet Union managed to build closer ties with the government in Kabul, taking advantage of the United States’ refusal to provide assistance to the country. A Soviet-Afghan military agreement was signed in 1956, and a large number of Afghan army officers underwent training in Moscow. The Afghan People’s Democratic Party, the Communist Party, was very influential, particularly in the entourage of Prime Minister Mohamed Daoud, until 1963. Between 1963 and 1973, King Zaher Shah pursued a policy of balance, until the coup led by Mohamed Daoud forced him to abdicate. However, this did not mean alignment with the USSR, and even the Afghan Communist Party was divided between two rival factions on rather obscure grounds. A new coup d’état on April 27, 1978, prepared by Afizullah Amin, seemed to tip the country into the socialist camp. The Revolutionary Council of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan, led by Nur Mohamed Taraki, declared that the country would follow the principles of Marxism-Leninism. The brutal repression of members of the clergy, inspired by the Muslim Brotherhood and Ayatollah Khomeini, which the Soviets paradoxically tried to limit, led to an uprising, including within the army. Despite strong reservations, the Soviets found themselves forced to prepare for direct intervention.

In passing, the author refers to the memoirs of Robert Gates, former director of the CIA, who points out that US support for the Afghan mujahideen actually began six months before the Soviet intervention. President Carter’s first directive supporting opponents of the pro-Soviet regime in Kabul dates from July 3, 1979, while the Red Army entered Afghanistan at the end of December. Clearly, the US intelligence services believed that their support for the Afghan rebellion would lead the Soviets to engage in the country and ultimately become bogged down there.

The leaders of the Red Army were not necessarily enthusiastic about this military intervention, which in reality had been clearly decided within the restricted circle of the Politburo, with Brezhnev, Ustinov, Andropov, and Gromyko.

General Sidos carefully analyzes the four phases of the Soviet war in Afghanistan. While the occupation was established between December 1979 and February 1980, the international consequences were particularly numerous, with the American response in the areas of grain and the Olympics, the mobilization of Arab countries against this attack on Muslims, and the reactions of China, all of which rejected the Soviet argument about the security of its southern border.

Very quickly, after initial successes against rebel troop concentrations, the guerrilla war waged by the mujahideen forced the Red Army forces to disperse.

Within the Soviet leadership, questions arose about the commitment to this conflict. From mid-1980 onwards, the Red Army had to reinforce its troops, bringing their number to over 80,000. However, 80% of the territory and 85% of the population remained outside the control of the Kabul government and Soviet forces throughout the war and until 1989.

The rapid attrition of the Red Army forces resulted in a significant gap between the stated number of troops and the number actually engaged. In 1985, there were theoretically 130,000 men present, facing 45,000 mujahideen. But in practice, taking into account the immersion within the population, which characterizes a guerrilla movement, the hostility of the population towards the occupying forces far exceeded the theoretical number of combatants. Despite widespread internal reluctance, Brezhnev’s successor, Yuri Andropov, continued to support the government of Babrak Karmal, who regularly denounced foreign interference by Pakistan and the United States in support of the mujahideen.

From 1982 onwards, the Reagan administration stepped up its support for the Afghan insurgents, who were now able to deprive the Soviets of some of their air superiority thanks to Stinger-type anti-aircraft weapons. It was not until Mikhail Gorbachev came to power on March 11, 1985, that Soviet policy began to shift. From 1986 onwards, Gorbachev put pressure on the Afghan communists to participate more in military operations, while promoting a policy of openness towards the opposition.

Soviet forces gradually withdrew from combat operations, but setbacks continued, particularly in the Panshir, with the actions of Commander Massoud. It was not until 1987 that the Afghan government officially announced a ceasefire and invited the opposition to negotiate. The country’s official name became the Republic of Afghanistan, removing the communist additions “democratic and popular,” which reflected a clear shift in policy. Very quickly, Soviet leaders began to consider a unilateral withdrawal, while the resistance increased pressure on Soviet forces, including by carrying out actions on the borders of Soviet Tajikistan.

The withdrawal of Soviet forces was officially completed on February 15, 1989, at 9:15 a.m

After discussing the different phases of Soviet action over nearly nine years, the author returns to his analysis of the insurgency led by the mujahideen. This insurgency was disparate, to say the least, with seven parties, Islamist and/or royalist, receiving quite diverse support. This depended on the ethnic origin of the fighters, their autonomy from Pakistan, and their membership in the Sufi brotherhood, for moderate Muslims. Loyalties in this area were quite uncertain and, of course, the question of financing and arms supplies remained decisive.

Pakistan is obviously a key player in the conflict, contributing to its radicalization, especially when the Soviet Union supported the irredentist project of Pashtunistan, straddling the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan. This was a period when the Pakistani regime resembled more an army with a state than a state with an army. The Inter-Services Intelligence, better known by the acronym ISI, obviously played a key role as an intelligence service providing direct military support to insurgents trained in Pakistan. Hekmatyar’s Islamic party was also widely supported by General Zia’s government.

The Soviet army was forced to adapt to the nature of this insurgency, which was largely embedded within the population. Mechanized operations proved ineffective, and it was not until 1985 that a real doctrinal change took place, with greater use of light infantry, elite units, and various special forces to strike blows against the rebellion. The objective on both sides was also to break the enemy’s lines of communication and supply, which constituted the bulk of military operations.

The departure of the Soviets, even though stabilization measures had been considered, did little to resolve the situation. The Kabul government quickly found itself isolated in the face of a rebellion that was determined to overthrow the Najibullah regime. Afghanistan experienced a three-year period of civil war between the departure of the 40th Red Army in 1989 and the fall of Kabul in 1992. The forces involved were part of the regular Afghan army, with significant equipment maintained by the Soviets, and the rebel forces.

In practice, the attempted coup against Gorbachev in August 1991 contributed to the fall of the regime, which was deprived of its main support. However, this did not end the civil war, as the various factions, notably the Islamists led by Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, sought to seize Kabul, competing with the factions led by Commander Massoud and Dostom. However, it was Rabbani, the leader of Afghanistan’s oldest Islamist party, who was appointed president, although his power remained fragile until he was ousted by the Taliban in 1996.

The conquest of Kabul was a major challenge for the various factions fighting in the city in early 1993.

There were numerous shifts in alliances throughout this period, particularly until the emergence of the Taliban in 1994. According to the author, this puritanical Sunni militia was born out of a local reaction to rampant crime and institutional corruption in Kandahar. Very quickly, they received the support of the Pakistani services, who were rather disappointed by Gulbuddin Hekmatyar’s missteps. The Taliban quickly managed to rally supporters of a return to order, former officers of the Afghan army, and gradually took control of Kabul on September 27, 1996. Commander Massoud was forced to retreat north, while the radical Islamist regime took hold. It was at this time that Osama bin Laden established his group in Jalalabad. In less than four years, the Taliban managed to take control of 90% of Afghan territory by directly subjugating its main opponents, such as Gulbuddin Hekmatyar’s group, the Shiite Hazara militia, and Dostom’s Uzbek movement. The Northern Alliance, made up of various factions, appeared to Westerners as a rather positive solution to the radicalism of the Taliban government. Commander Massoud’s war against the Taliban lasted from 1996 to 2001, but despite their extremism under the leadership of Mullah Omar, the Taliban enjoyed international recognition from Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, and the United Arab Emirates. The United Front, another name for the Northern Alliance, managed to launch offensives against the Taliban regime from 1998 onwards, which quickly became unpopular. In March 2001, the destruction of the Buddha statues in Bamiyan further isolated the Taliban regime. However, on September 9, 2001, Massoud was assassinated, marking, two days before September 11, the beginning of the global war on terrorism.

This civil war, which took place between 1989 and 2001, demonstrated, conversely, that it was impossible to conceive of a harmonious future for this country. Relatively united in their fight against Soviet occupation, the various Afghan factions, Islamist movements, and supporters of the former kingdom quickly became divided over the issue of power. The role of global jihad, which sought to establish a rear base in the country, contributed to worsening the situation, ultimately leading to US intervention after the September 11 attacks. Regional foreign powers, notably Pakistan and, to a lesser extent, Iran and India, also sought to exploit the various factions, taking advantage of the departure of Soviet troops.

Part Three: 20 years of American war in Afghanistan

The episodes in this third part of the book are obviously closer to home, but it is worth recalling the main stages.

The starting point for the American intervention was, of course, the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. On August 31, 2021, two observations were made: the failure of the nation-building project and the military impasse, despite the significant resources deployed.

With hindsight, the author questions the justification for the American intervention in retaliation for the attacks on the World Trade Center. None of the terrorists who carried out this planned attack were Afghan nationals, and a priori it was not part of the Taliban’s political agenda. The United States had nevertheless imagined a form of normalization of the Taliban regime between 1996 and 2001. In 1998, a cruise missile attack was carried out in response to the attacks in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam, which undoubtedly contributed to inspiring jihadists throughout the Middle East.

The initial objective was to destroy Bin Laden’s movement and its supporters. President Bush’s ultimatum was rejected by the Taliban, who made it very clear that they would wage jihad until the Americans left if they intervened in Afghanistan. They kept their promise.

Among the factors that must be taken into account to explain the United States’ entry into the war in Afghanistan is the lack of anticipation of the September 11 attacks. As General Sidos explains, the warnings from the intelligence services had been clear, but did not seem to have prompted any particular protective measures. However, FBI information explicitly mentioned the possibility of aircraft hijacking.

Just before the September attacks, the United States had also considered strengthening its support for the Northern Alliance, including through direct actions, secret or otherwise, against al-Qaeda.

Between September 12, 2001, when the terrorist attacks against the United States were declared an act of war, and the actual military intervention at the end of the year, various scenarios were considered. The memory of the Vietnam War and the quagmire it created was still fresh in people’s minds, and the possibility of a full-scale ground offensive was not necessarily considered at the outset. The initial plans for action were based mainly on special forces operations combined with greater support for the Northern Alliance engaged in the fight against the Taliban. Initially planned as a CIA operation, the US intervention, no doubt for reasons of internal power relations, involved the armed forces more directly. The desire to combine action in Afghanistan with direct intervention against the Iraqi army is obviously not unrelated to this development.

More specifically, the US command in the Middle East, in charge of operations in that region, does not really have the conventional means for a long-term ground engagement. The proposed scenario combines the action of the Green Berets and special forces with precision strikes on the Taliban’s entire military apparatus, with the aim of bringing down the regime. But once again, Dirk Chesney and Donald Rumsfeld’s desire to open a new front in Iraq changed the initial plan. It would appear that General Franks, in charge of CENTCOM, expressed strong reservations on this matter.

The US military operation in Afghanistan took place in several phases. It may seem easy in hindsight to criticize it, but the complexity of the Afghan theater should encourage commentators to be modest.

The operation began with the objective of eradicating the Al-Qaeda terrorist base in the country, but the expansion of the conflict to Iraq very quickly changed the situation. The Bush administration’s goal was to demonstrate that it was possible to bring about positive change in this part of Central Asia and, beyond that, in the Middle East. The expression “booted Wilsonism” is not inappropriate to characterize this policy. Similarly, forcing Pakistan to participate in the fight against terrorism, including through the use of threats, is not necessarily negative. However, the United States very quickly reverted to methods that had led to failure in Southeast Asia, namely the deployment of forces without any real medium- or long-term political objectives. Only 15% of the huge sums of money spent on contributing to the economic development of one of the world’s poorest countries was actually used for that purpose. As a result, the Taliban, whose departure at the end of 2001 was not greatly regretted by the population, were able to rebuild themselves fairly quickly in their Pakistani sanctuary. The elusive Mullah Omar emerged as a traditional Afghan religious hero who managed to rally around him the various factions that had gained power during the civil war. This enabled them to launch an offensive in 2006, which had been in preparation since 2003, resulting in the systematic harassment of Afghan national forces, local police forces, and anything else that contributed to the political weakening of President Karzai.

The foreign presence quickly came to be seen as an occupation, which paradoxically led to the need to increase troop numbers in order to achieve the goal of rebuilding the nation. The Taliban groups succeeded in creating insecurity in the various areas where they were established, which contributed to the population’s withdrawal of any support for the Western forces. American attempts to establish a lasting presence, particularly in what has been called the Valley of Death in the Korengal sector, ended in failure.

The various military leaders who have succeeded one another at the head of the US forces, but also of NATO, whose initial missions are different, have all recognized the impasse, especially when we consider that President Karzai’s entourage has ambiguous positions towards the Taliban, but also towards drug trafficking. In 2008, weariness and fatigue led to a resumption of the war, against a backdrop of the rediscovery of the doctrine of counterinsurgency.

Alongside the increase in military action, particularly in the Kandahar region, the United States stepped up its drone attacks, dealing serious blows to al-Qaeda’s chain of command. However, despite an increase in troop numbers during the surge, the Taliban remained strong, President Karzai’s regime was still largely corrupt, and on June 23, 2011, President Obama began the process of repatriating some of the troops. The surge may have weakened the Taliban’s forces, achieving a tactical victory, but it had no strategic impact. The counterinsurgency doctrine advocated by General Petraeus is gradually being called into question. Tensions with Pakistan are mounting, and the raid against Bin Laden and his elimination do not really improve the situation.

American military successes may have suggested that negotiations could indeed begin, but this took time, especially since the United States demanded disarmament and the resumption of contacts with Hamid Karzai’s government as a prerequisite. For the Taliban, the withdrawal of American troops is obviously a prerequisite.

The establishment of a national Afghan armed force is also an essential objective for the pacification of the country. It is easy to see that moral strength is not the essential characteristic of this Afghan national security force. Incidents, sometimes serious, occur in the cohabitation between foreign troops and Afghan security forces. Some of their members turn their weapons against coalition forces.

The actual withdrawal began in 2014 with the French forces, in line with a commitment made by President François Hollande, but it also affected the other coalition forces, including the Americans. The presidential election took place in 2014 and the results were immediately contested. The second round pitted Abdullah against Ashraf Ghani, a Tajik against a Pashtun. The election takes place on June 14, 2014, with Abdullah Abdullah declaring victory with 47% of the vote and denouncing the fraud from which his opponent allegedly benefited. An agreement is finally reached to share power between the presidency and the executive branch. This takes place against the backdrop of a Taliban offensive, which stepped up its attacks to establish new safe havens in Helmand and Kandahar. The Afghan National Army did not show much fighting spirit, and it would appear that local police officers were the first victims of these battles.

The emergence of Islamic State in Iraq and Syria indirectly relativizes the radicalism of the Taliban, reinforcing the idea that negotiation with them is possible, especially as Western forces are increasingly less present in combat zones. US air strikes are much less frequent than in the past, and casualties are very high: in 2015, more than 20,000 Afghan soldiers and police officers were killed or wounded across the country. The debate over the withdrawal of US troops, which has been going on for three years, is bogged down, and Mansour, the Taliban leader, is conducting large-scale operations that are further consolidating his authority in part of the country. The Islamic State of Khorasan returned in 2017 and 2018 and managed to establish cells in Kandahar, Jalalabad, and Kabul. The Taliban found themselves facing an adversary in the escalation of extremism and terror.

With the Trump administration, during its first term, negotiations began in early 2018, and the Taliban declared themselves ready to negotiate with the United States as long as the Afghan government was excluded from the discussions.

The Afghan-born US ambassador, Zalmay Khalilzad, was the negotiator of the Bonn Agreement in charge of negotiations with the Taliban. Very quickly, Donald Trump exerted pressure, with Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, to consider a rapid withdrawal of forces. The negotiations in Doha put an end to offensive military operations against the Taliban, which obviously paved the way for the rapid withdrawal of the Afghan National Army and, ultimately, the withdrawal of all Western forces.

The toll of this war is obviously very heavy, and after 20 years of military intervention and the deployment of enormous resources, the United States was forced to withdraw. Certainly, terrorism, to use Donald Trump’s expression, “is no longer a problem in Afghanistan.” But the bottom line is that an entire people finds itself trapped under an obscurantist regime that has not changed its ideology one iota. However, unlike al-Qaeda or ISIS, the Taliban are not seeking to export their political model. Nevertheless, at the cost of 20 years of war, they have been able to maintain their position and ultimately prevail. They undoubtedly have to contend with pockets of Islamic State opposition, but overall, they seem to be holding the country together for the time being.

Nevertheless, the war in Afghanistan remains a reference point in the study of military issues. The adaptation of a Western doctrine, with combined arms warfare, does not seem to have yielded good results. Transforming Afghan warriors into soldiers of a regular army, based on the Western model, was undoubtedly a major mistake. Numerous military successes against the Taliban were not enough to win the hearts of the local population. It must also be acknowledged that Afghan politicians were more concerned with their own interests than with a global vision for the country’s development.

Overall, this book is very comprehensive in its coverage of military operations, but it probably lacks an ethnological study to truly understand what may have happened in these Central Asian mountains over the past 20 years. No doubt the first two parts of the book, devoted to the British wars and the Soviet intervention, should have been written before the Western world, after striking the terrorist cells behind 9/11, embarked on an intervention that proved fruitless. They might have avoided some of the disillusionment.