The term “right” is rarely used in connection with Islam or with the governments of Muslim countries; the very question seems odd, whereas defining Catholic right-wing movements poses no difficulty. Political history in Muslim lands has unfolded according to criteria quite different from those of contemporary Europe. The conditions for the rise of the European right were never present in Muslim countries. This produces a wholly different relationship to history and politics.

Article published in Issue N59 Droite. La nouvelle internationale ?

The Isolation of the Liberal Right

The liberal bourgeoisie in Islam struggled to emerge in the 18th and 19th centuries. Unlike the modern European city, the Muslim city was not a place where capital accumulated and could be reinvested; the rural economy was extensive and pastoral, and demographic growth stagnant. Agricultural rent was absorbed by Ottoman taxation and the military aristocracy, benefiting neither the rural middle class nor the merchant elite.

Economic take-off did not occur through interaction between cities and countryside or through the rise of an urban bourgeoisie. The latter had no access to political power, monopolized by military elites, and therefore could not create a self-conscious civil society.

Intellectuals and merchants were marginalized in the modern Islamic empires in favor of the ulama, the religious scholars—a privileged, conservative caste, but powerless against state violence. There was thus no separation between religion and state conducive to the emergence of a secular society.

For the liberal right to emerge, it required the light of secular education and Enlightenment philosophy. Yet while literacy in the Qur’an was widespread in North Africa’s mosques before colonization, it was a religious education, lacking the secular application that might have fostered artisanal or capitalist systems.

When it finally appeared in the second half of the 19th century, the bourgeoisie had no autonomy: economically, it was tied to European industrialization and capital; politically, it operated only in the margins left by military elites or monarchies; socially, it could not challenge the ulama’s legal monopoly.

Inevitably, it had no party to represent it. It could, however, invoke the Qur’an to defend individual responsibility, a value rooted in the European right. Man is indeed held accountable for his acts, as numerous verses emphasize beneficence, good deeds, and the soul’s disposition; behavior is often weighed against God’s forgiveness, as if the two went hand in hand (e.g., Surah 2:225). This recalls the attitude of 19th-century Christian employers and their paternalism.

A Monarchist Right?

In Europe, the trauma of a monarch’s death and the hope of restoration underpinned right-wing politics throughout the 19th century, whereas in the Muslim world, reference to monarchy was by no means indispensable. The Qur’an is not a political text. Its rare allusions to governance do not sketch even an idealized image of a Muslim state. There is the “verse of the emirs” which makes obedience to rulers a religious virtue, but it sets no applicable framework: “O you who believe, obey God, obey the Messenger, and those among you who hold command” (4:59).

When the book lists the qualities of believers, it mentions only moral and religious virtues, adding that “their affairs are conducted among them by consultation” (42:38), thus leaving temporal matters to the self-governance of human groups. Later tradition, in the 9th and 10th centuries, established the caliphate as the obligatory theocratic reference, drawing inspiration from Byzantine and Persian models of the ideal sovereign.

The trauma of the caliphate’s collapse dates long before its official abolition in 1924. With the fall of Baghdad and the Mongols’ execution of the caliph in 1258, the Abbasid dynasty collapsed, and with it the political model based on a caliph from the Prophet’s tribe. Yet Muslim societies quickly adapted: while some scholars still dreamed of restoring the caliphate, pragmatism prevailed—sultanates in the East, emirates in Africa, soon kings in Egypt, and later republics.

Islam thus fully absorbed political disillusionment and relativism toward rulers. God may choose any government; only respect for order matters. As the great rigorist scholar Ibn Taymiyya stated in the 14th century: “Sixty years under a tyrant are better than one night without a tyrant.”

Can one then speak of an Islamic royalism? The few nostalgics of the Ottoman dynasty or Iran’s Pahlavis belonged to their circles or profited from their policies. Iran’s 1979 revolution was republican from the outset, with God’s will confirming popular will (albeit manipulated). Nowhere did monarchism form a movement, and even in Morocco the monarchy is not debated but taken for granted. Only ISIS theorists imagined a caliphate’s return, but in such apocalyptic violence that it cannot be considered a political movement.

Conservatism Across the Spectrum

One cannot deny, however, the strong conservatism present in most Muslim countries, combining many traits of Europe’s right-wing conservatism: attachment to religious values, concern to avoid social unrest, and an emphasis on traditional education. In practice, however, states and political movements adapt these criteria: the UAE and Saudi Arabia in the past decade have relied on globalized youth to reform religious and moral systems while tightening political control; the Muslim Brotherhood distanced itself from old elitist, literary education and embraced modernity; Sufi sheikhs in Africa still preach moral rigor but serve as forces of integration and negotiation in fractured societies. Conservative right-wing criteria apply only imperfectly.

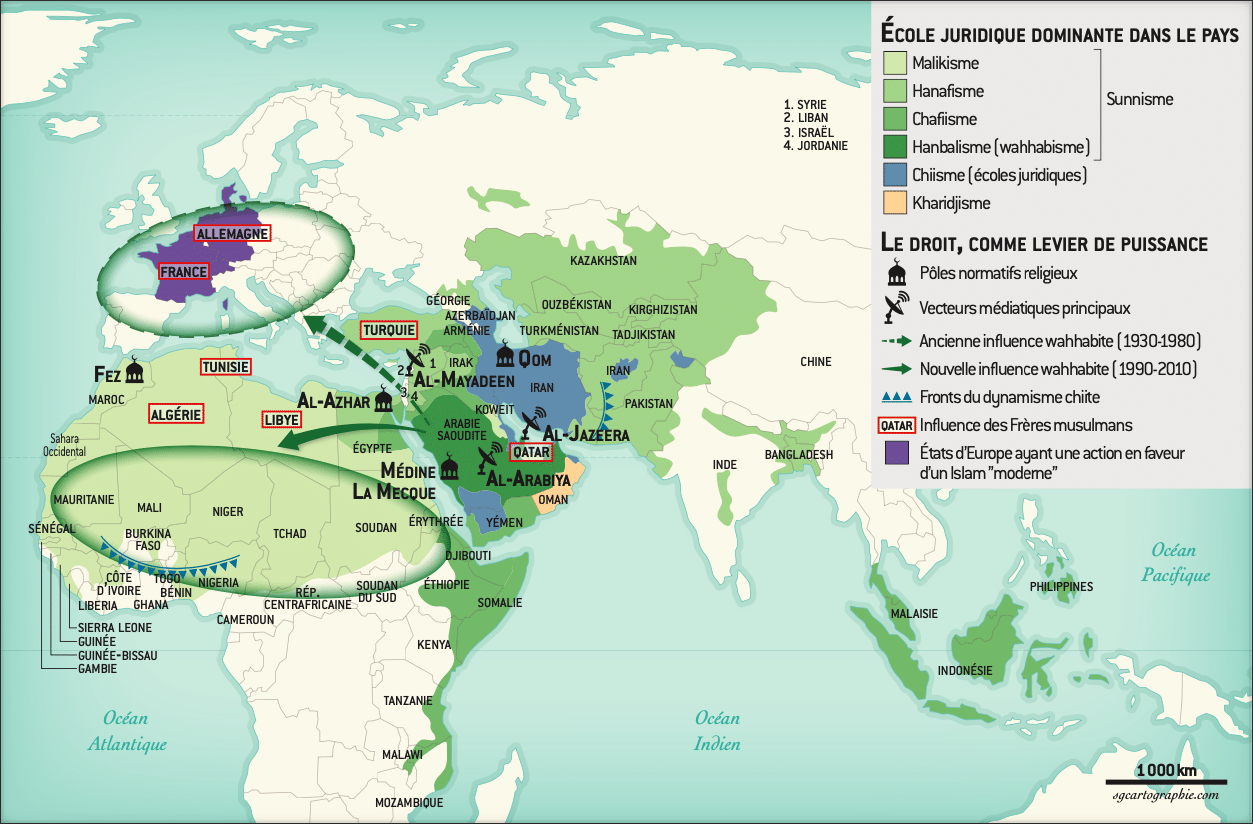

Indeed, legislation in Muslim countries diverges from Western progressivism on social issues and aligns with “bioconservatives,” generally placed on the right. The same is true for Muslims in Europe seeking halal rulings on abortion or end-of-life issues. Typically, when a societal issue arises, Muslims of all leanings take individual positions, before representative bodies in France (CFCM) or the European Council for Fatwa and Research (ECFR) are consulted. The ECFR, a private foundation created in 1997, based in Dublin and directly influenced by Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood ideologue Yusuf al-Qaradawi (1926–2022), plays a leading role.

Despite its avowed conservatism, the ECFR is Europe’s only significant authority in Muslim law, and its rulings are inevitably read, if not always followed. When consulted, it organizes meetings and public conferences with experts whose opinions are advisory, before issuing a context-specific fatwa, generally restrictive. This is then echoed, paraphrased, or adjusted at various levels. A Muslim legal opinion thus emerges, narrowing adaptation and remaining in place until a new social demand arises.

If opposition to active euthanasia is clear among European Muslims, it differs little from the stance of Christian churches and proves equally marginal in legislative debates. Beyond end-of-life issues, French Islam must interact with international organizations, often private or Gulf state-backed, that foster the homogenization and globalization of a “middle-ground Sunni Islam,” though with strong moral conservatism. It is not a progressive Islam, and in this sense it could be described as “right-wing.”

Islamic Capitalism

By contrast, there is near-unanimity among elites in Muslim countries in favor of commercial and stock-market capitalism, combined with Keynesian-style state intervention in the economy (though much less on the social front). Despite the Qur’an’s distrust of usury, all legal devices have been devised to enable national and corporate enrichment.

Since the 1970s, a business bourgeoisie has emerged, participating in the market economy. It is rarely an industrial bourgeoisie, since most industrial investment comes from international groups or state-owned enterprises.

Thanks to ties with political elites, it has benefited from public monopolies (construction, hydrocarbons, minerals, etc.) and acted as a bridge to international capital. It has often allowed modest trickle-down to middle classes—e.g., in Egypt or Syria, those closest by geography, religion, or clan. In Algeria and Saudi Arabia, this trickle-down was indexed to oil prices above $80 a barrel, but the prolonged fall in prices prevented real redistribution.

The promises of a globalization that would benefit all collapsed with the 2008 crisis, as middle classes fell into poverty, foreshadowing the uprisings of 2011–2012. With the collapse of Syria, Iraq, and the Tunisian and Lebanese economies, there was a cautious return to predatory economics and a liberalism benefiting a minority connected to global markets. If one speaks of right-wing liberalism here, it is profoundly authoritarian and clannish.

A Broadly Shared Authoritarian Nationalism

Finally, nationalism—often considered a right-wing concept despite its complex history—is a widely shared ground, easily mobilized by contested regimes (e.g., in Algeria or Egypt) and immediately effective against external threats: Israel for Lebanon, the U.S. for Iran. It is, however, difficult to justify when invoked in the name of Islam or against neighbors who are likewise Muslim, Arab, or from the same tribes (e.g., Saudi Arabia vs. Qatar in 2017; Algeria vs. Morocco in 2024).

Nationalism has been alternately instrumentalized and contested, since it fractured the unity of the Muslim ummah; in reality, only Salafists still call for the collapse of nations. This was also ISIS’s claim.

Nationalism is accompanied by militarism rarely denounced in society, except by a few closely monitored pacifists or rare Sufi currents such as the Ahmadiyya—widely contested within Islam—that defend an Islamic pacifism. One can thus call for Islam’s common victory against Israel or the U.S., while appealing to nationalist rhetoric, evident in speeches by Turkey’s President Erdoğan or the aging militants of Algeria’s FLN.

A European Islam Marked by the Left

If European Muslims are consistently placed on the left in opinion polls, it is not because of the Qur’an or the religious definitions transmitted since the 7th century, but because of social issues, which remain primary in electoral choices, as most Muslim citizens are still of modest background. Communities also inherit the memory of colonization, a reason for leaning toward decolonial movements or opposition to Israel, seen as a neocolonial archetype.

Similarly, socialist or Marxist references were prominent in Muslim countries until the 1990s, largely due to the twin contexts of decolonization and the Cold War, with many regimes siding with the USSR against their former European colonizers—Algeria, South Yemen, Syria, Indonesia, for example. They had little difficulty turning to the U.S. when the Eastern bloc collapsed, Egypt having led the way as early as 1978.

Muslim countries thus provide different keys to political analysis than the left/right divide, and their difficult ideological alignment with what in the West is called “the right” is mainly hindered by the weight of recent history rather than by the rare political approaches that appear in the Qur’an.